The Review/ Feature/

An Ever-Changing Detroit

The city's cinematic portrayal shows the future has a silver lining

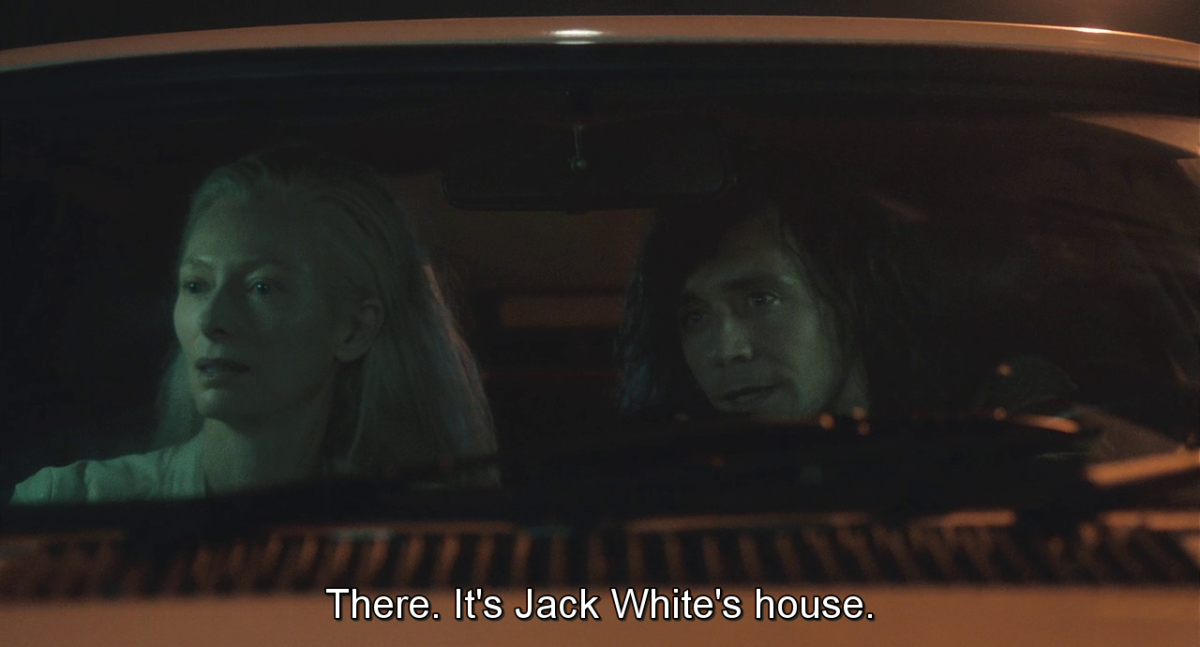

“So this is your wilderness: Detroit,” says Eve (Tilda Swinton) to Adam (Tom Hiddleston), early in Jim Jarmusch’s elegiac romantic drama Only Lovers Left Alive. A mournful recluse, Adam explains that he was drawn to the loneliness of the Motor City, where the rows of foreclosed houses and abandoned industrial spaces suggest a metropolis evacuated at midday. “Everybody left,” he says, sadly.

As a backdrop for a story about fabulously dissolute bloodsuckers futilely waiting out their own immortality, Detroit is almost too perfect a fit. Jarmusch makes it appear like a city of the undead. In interviews, he explains he was drawn to that oddly posthumous quality. “When I was a child it was almost mythological, the Paris of the Midwest,” he told Screenprism. “And now what’s happening with Detroit is very tragic and sad. I was drawn to it, visually and historically, for its musical culture, industrial culture and post-industrial visual feeling.” In one of the film’s best jokes, Eve, who has been alive for centuries and thus has a deep pool of personal favorite artists to choose from, singles out local hero Jack White for gushing praise.

Shot in shards of hard, glinting light and deep shadows by the gifted French cinematographer Yorick Le Seaux, Only Lovers Left Alive certainly takes advantage of the surrounding dilapidation - it may be Jarmusch’s most beautiful-looking movie. But it’s worth asking if the film’s civic homage is an empathetic portrait, or a form of vampiric exploitation. David Robert Mitchell’s genre pastiche It Follows (2014), with its late passages of alienated teens driving past spooky urban wasteland real estate, might’ve been too much. For several decades, Detroit has been the go-to location for filmmakers looking to comment on the decline of the American empire.

Paul Schrader’s ferocious Blue Collar (1978) was the film that started the trend. While its heroes, played by Harvey Keitel, Yaphet Kotto and a never-better Richard Pryor, are gainfully employed on a downtown assembly line, they’re so fed up with their wages and mistreatment at the hands of middle-management that they plan to rob the union office. The bleak, brutal joke of Schrader’s film is that there’s no money in the safe. In fact, the real bad guys turn out to be connected to the auto workers union, a locus of corruption. From its title on down, Blue Collar evinces the desperation of a city whose post-war prosperity is being greedily stripped down to the bone.

By the late 1980s, it appeared that Ronald Reagan’s “Morning in America” hadn’t hit Michigan, which was cast in perpetual twilight and stuck fast at the (Chapter) Eleventh Hour. Two of the most significant American movies of the era addressed this disparity in different ways. Paul Verhoeven’s RoboCop unfolded as a near-future parable in which heavy industry both imperils and redeems the state’s capital city. (The film rapaciously annexes the city into “old” and “new” sections by unscrupulous developers.)

Michael Moore’s Roger & Me (1989) dispatched its director to ailing, working-class Flint to harangue General Motors honcho Roger Smith for leaving its newly unemployed inhabitants high and dry. Both films were works of broad, apocalyptic satire, featuring vicious corporate villains and crowd-pleasing superheroes; for me, Moore’s performance as a baseball-hat-clad class warrior was more robotic and less soulful than Weller’s work as a fallen rop remade in the slate-grey image of the city that destroyed him.

The recent, and still-delayed plans to build a statue of RoboCop in downtown Detroit are touching and fully warranted. If Philadelphia can turn a slab of bronze resembling Sylvester Stallone into a tourist attraction, there’s no reason Officer Murphy can’t stand guard over his own citizenry. Besides, most of the other key Detroit movies are self-erected monuments to the greatness of their native sons, real and imagined. In 8 Mile (2002), Marshal Mathers turned his already famous trailer-park adolescence in Warren, Michigan – Metro Detroit’s largest suburb – into the cinematic equivalent of a fight song.

A nicely-turned piece of hero (self)-worship, 8 Mile (directed by Curtis Hanson) ends with Mathers’ B. Rabbit pridefully defending his turf. (“Everybody in the house from the 3-1-3/put your motherfucking hands up and follow me!”) Yet, the implications were clear: the real Slim Shady was already off to the bigger and better things his onscreen alter-ego had contemptuously disavowed. This sense of pathos for your hometown was even more ersatz in Clint Eastwood’s Gran Torino (2008), in which the director also starred as Walt Kowalski, an aged Korean War veteran living in Highland Park, eager to reconcile the profound decay of his neighbourhood with the influx of Asian immigrants.

In Nick Schenk’s baldly symbolic script, Walt’s 1972 Ford Gran Torino – a car historically branded after the city of Turin because of its reputation as the “Detroit of Italy” – represents the same old-fashioned American values as its owner. There is an incredible (some might say transcendent) vanity in the film’s climax, which finds Walt literally adopting a Christ pose as he dies for the sins of a pack of Hmong gang-bangers. Eastwood’s recent comments about the scourge of political correctness belie Gran Torino’s too-cozy vision of an America where racial epithets and condescension are necessary stitches in rough-hewn social fabric. One wonders what the residents of Highland Park (selected as a filming location because of copious tax credits!) thought about being used as a staging ground for such overt self-mythologizing.

Standing on firmer ground are the documentarians who’ve taken on Detroit as a subject: both Heidi Ewing and Rachel Grady’s Detropia (2012) and Peter Mettler’s The End of Time (2014) examine the social, economic and architectural conditions of their host city. Detropia is more explicitly a city-film, profiling three residents – a video blogger, a nightclub owner and a union organizer – who narrate the mix of problems and opportunities that have arisen in a literally and figuratively flattened municipal space and acknowledge the concurrent rise of artistic subcultures therein.

There are similar stirrings in Mettler’s movie, which tempers its metaphysical inquiries with the interesting information that Detroit is one of the birthplaces of techno music. The Canadian director transforms the city from a tomb into a psychedelic house party, ringed with lush community gardens. To quote Eve in Only Lovers Left Alive: “There’s water here. This place will bloom.” In a movie full of rueful jokes, the idea that it takes a vampire to recognize signs of life in Motor City may be the slyest – and perhaps the sweetest as well.